Visit to DC

This was an extraordinary visit to the capital. I drove to DC to meet up with an advocacy group called Burn Pits 360. This group is a small nonprofit from Robstown, TX that has been advocating for, among other things, elimination of burn pits, getting veterans accurate medical diagnoses, and disability compensations. They are seeking to expand their political footprint by training advocates across the country. My goal was to get a better feel for them and their organization. A second goal was to meet the veterans affected. I was confident I could find at least a few such veterans at a congressional update briefing that Burn Pits 360 was hosting. The congressional update was by a panel of doctors and a lawyer that advise Burn Pits 360.

Dr. Robert Miller, one of the panelists, was the first physician to tie in the diagnosis of constrictive bronchiolitis to soldiers over a decade ago. He gave his story in which he tells of how he worked to find a diagnosis in these otherwise healthy soldiers. These men had already undergone all conventional testing, which continued to show normal results. Dr. Miller took the drastic and unconventional approach of performing open lung biopsies. Every biopsy was abnormal, and the majority of these results showed bronchiolitis. He went on to explain that when he shared these results with the Army he was told to not share them. The Army went on to attack his credibility and the creditability of his results. Dr. Miller was told that if he shared these results with anyone that he would never be able to care for an active duty soldier again. Dr. Miller responded by publishing his data in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Anthony Szema, the same doctor who believes I have the same pulmonary injury as so many other veterans, was present and laid out the science of the pulmonary injury. He showed slides from soldiers whose lungs have been biopsied and which contained titanium, iron, and other heavy metals. Dr. Szema explained how these metals are vaporized in combat explosions, rendering them airborne to be inhaled. He also examined the results of military air sampling that the military argues do not pose a threat. He argued that the sampling was flawed and that even the data that has been collected does show evidence that the air affected by burn pits is dangerous.

Dr. Thomas Woodson, a new physician to the Burn Pits 360 team examined the socioeconomic impact of military burn pits. He reviewed the political impact that Agent Orange had and continues to have with the relationship between the United States and Vietnam. He also explained how hypertension in the military population has significantly exceeded the national average. Family members of those serving in the military have also been seen to have a greater degree of hypertension.

Dr. Steven Coughlin worked for several years as a senior epidemiologist in the VA department of Public Health. He published a paper in Augusta that examined how military cancer deaths supersede deaths from the larger group of veterans affected by bronchiolitis. Dr. Coughlin left his position in December, 2012 citing ‘serious ethical concerns’. Dr. Coughlin has previously gone on record reporting that large scale studies are typically not released if the information in them does not conform to the message that the VA wants to show. He has also stated that when studies that could embarrass the VA are released, the data is manipulated in such a way as to make it unintelligible.

Kerry Baker, a lawyer with the practice Chisholm, Chisholm, and Kilpatrick shared how he has represented veterans with disability claims that the VA had denied. He detailed how in challenging the VA cases he has continually found that at least half of the cases he has fought could have been avoided if the VA would simply train its staff in the existing guidelines for handling veteran claims and then follow those guidelines. Baker has consistently found that the decision makers are usually nurse practitioners or physician assistants who have absolutely no background in treating the diseases about which they are making decisions of compensation.

In attendance at the update were several senators and representatives. Before this update the panel had presented for SVAC (The Senate Veterans Affairs Committee). This has been the first time that these doctors have been able to present their data to Congress in a meaningful way. Previous meetings of this nature have only included information provided by the VA.

The POWER of a good story

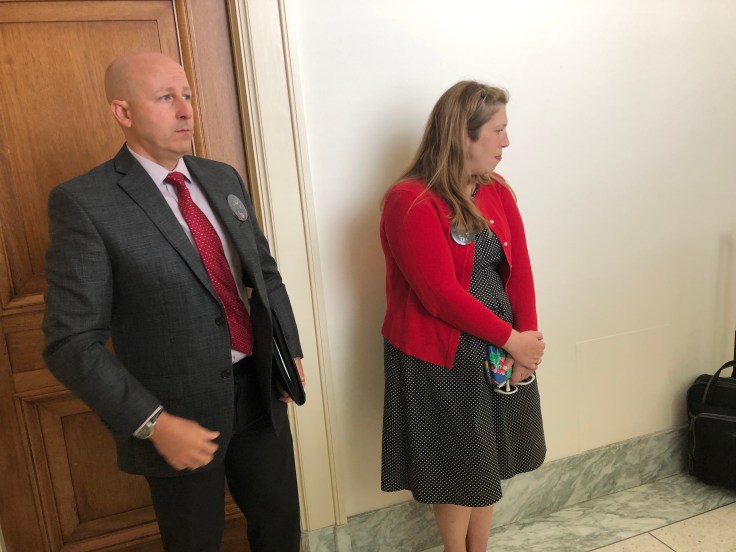

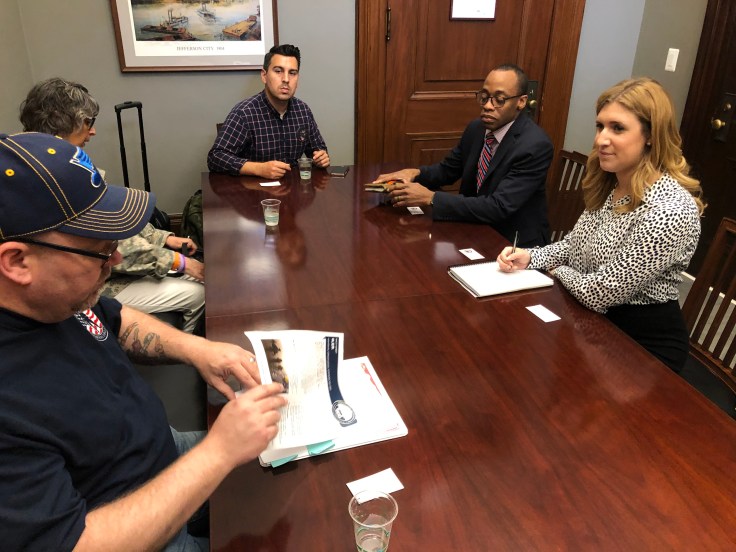

The following day a group of us went back to the Capitol building. We met with the staff of the Ohio 7th Congressional District, Representative Bob Gibbs, Senator Roy Blunt of Missouri, and directly with Rep. Blain Luetkemeyer of Missouri’s 3rd District. There were many learning experiences for me.

“This is a bipartisan issue!” was one of few responses I remember directly hearing from Representative Luetkemeyer. Will Wisner, Program Manager for Burn Pits 360, laid out the argument for HR 1001 (Allowing family members access to the VA burn pit registry and the ability to add deceased soldiers) and HR 1005 (legislation to include constrictive bronchiolitis as a presumptive positive for receiving VA compensation and health care). He explained how there has been little Republican support for these bills so far. Explanations followed of how service members have been committing suicide, citing illness that no one would believe they had, and that he strongly feels this feeds into the high numbers of military suicide. Will then asked those of us present to share our stories. Rocky, a former Airman shared his story of how he is still trying to find a doctor who can give a reason why he can’t walk and keep his breath, as well as why he gets intermittent mental fogginess. Susan shared about her son-in-law who is dying of a series of cancers.

I remained silent up until the point that Will asked me to share how I had come to be in this room. I simply recounted my story of progressive weakness and shortness of breath. I also added the story of my pneumonia from 2015 and that one of the Columbus doctors I know felt that my time in service would explain a lot to him about why that hospitalization had been so severe. I went on to add that examining statistics of sick veterans from Desert Storm/Desert Shield and assuming the same percentage of veterans becoming sick for current conflicts would could be around 1,000,000 affected service members. I explained that there was no way to know if this was an effective number but that there have already been over 173,000 service members who have become sick enough to register on the VA Burn Pit Registry. I also included that given it took 10 years for me to have any problems significant enough to be hospitalized.I inferred that the numbers of sick patients is likely to rise. Representative Luetkemeyer breathed out an exclamation, now looking visibly pale. He then acknowledged the intent of HR 1005.

Our meeting finished and we left. Will told the staff that he would be having a town hall meeting back in Missouri, to which the representative’s staff appeared to have a keen interest in how they could get him there. I reflected on how I had shared theoretical numbers that have no way of being verified and that it had been clumsy of me. This had also been my first time in such an environment. Still, having been a new experience I would say that it just means that there is plenty of time for me to learn how to improve.

Since being hospitalized I have been up against being repeatedly told that I have no real problems or that my only problem is this asthma that none of my providers have been able to prove. More concerning to me has been the way in which providers have acted around me. There has been a good deal of attitude I have felt off of said providers. I have heard numerous remarks and direct statements about anxiety. One EMS recently told me “you just need a Valium!” This statement is now a running joke between my wife and I. For over a year I have felt a large number of providers looking at me like my problem is all in my head and that I simply just can’t handle emotions (despite working in an ICU with trained coworkers who have indicated a significant level of concern for my wellbeing). I recently started looking for a new primary care provider. My previous one smirked, rolled her eyes and explained to me that she knows that my problem is just asthma and that I ‘may’ be having panic attacks with them. She had told me that she could send me to get a broncho-provocation test. If she had been slightly more interested in considering anything I had to say she might have remembered that she and her partner had sent me to 2 pulmonary doctors and that I have had 2 broncho-provocation tests that cannot identify what has been happening. Ironically, I had just been trying to ask her for guidance on how to deal with a dismissive medical community.

Coming to DC allowed me to see people who have all had the same story. They have symptoms that no one knows what to make of and been told that their problems were either asthma, psychological, or both. I wonder how many veterans simply have faith in the system that tells them that they are the problem.

I reflected on all of these thoughts and events as I drove home. For so long I have had to fight the feeling that I am the problem. Looking back at the expression and demeanor of Representative Luetkemeyer I realized for the first time how much power is in my story and the stories that these other veterans tell. Now the question is what to do with it.

(The above should image is from our base FOB Marez. The sand surrounding it was part of our half mile trek for food each meal. The chow hall was destroyed before Christmas, 2004 by a suicide bomber whom detonated at lunch time.)

(The above should image is from our base FOB Marez. The sand surrounding it was part of our half mile trek for food each meal. The chow hall was destroyed before Christmas, 2004 by a suicide bomber whom detonated at lunch time.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.